Brett Crawford: Character Building.

LA-based artist Brett Crawford didn’t go to school to learn how to paint and draw. When he entered the educational institution that would change his life, they flat-out told him, “You’re not going to be doing art here. You already know how to do that. We’re gonna teach you how not to be an asshole. Once you figure that out, then you can go back to your art.”

The school in question was the Delancey Street Foundation, a California residential education centre for ex-convicts, addicts and the homeless. “In 2007, a judge gave me an opportunity, a choice: I could either to go to prison for twelve years, or go to this program for two years,” Crawford explains. “I’m not great with math, but I’ll take two years instead of twelve, you know?”

Crawford was initially skeptical about the program, and maybe more so, doubtful of himself. “I was in this rather long period of my life, getting in trouble, going to jail, then more drugs, more jail,” he says. “I ended up spending, primarily, the first half of my adult life in jail, in prison, for drug charges or for crime, and I didn’t think that I was ever going to get out of that.”

Navigating a challenging childhood, art had always been his escape. “When I was young, my house was full of really crazy domestic violence and things like that. Art was a way for me to create my own space where I was safe and I was in control,” Crawford recalls. “I couldn’t control the violence in the household, I couldn’t control the things happening to my mother, to me, in the house, but I could control this one little space.”

His mother encouraged his artistic pursuits. “She’d give me pencils and papers to draw with, so I spent a lot of time in that little space. Because it was my little space.” But when he got into drugs and the criminal activities that often run in tandem with that lifestyle, his creative pursuits fell by the wayside.

“My art went away for a long time,” Crawford says. “I’d lost my moral compass. I became the worst version of myself.”

At Delancey Street, residents are offered vocational training in fields such as hospitality, construction, computer technology, landscaping, construction, truck driving and carpentry. Just as importantly, they’re taught how to be better communicators, how to resolve conflicts, solve problems, manage their time, money and relationships. “For me, I didn’t know if it was gonna work,” Crawford says. “But I went in, and I fell in love with the people.”

Though the courts had mandated he spend two years at Delancey Street, Crawford ended up voluntarily staying for five. After a good chunk of time learning “how not to be an asshole” himself, he then set about helping others do the same.

“I travelled all over the United States, going into institutions and prisons and talking to people, kind of helping other knuckleheads like me, fix their lives,” Crawford says.

“The goal is to become just a regular, hardworking, kind, honest, decent human being. That’s the goal. If you can do that, if you can figure out a way to fix the person, whatever else it is you want to do in your life, you’re much more likely to get it done.”

What Crawford had always wanted to be was an artist, but towards the end of his tenure at Delancey Street, he was told to hold fire. “I had a mentor in there named Dugald Stermer, who was an illustrator.” [A highly accomplished illustrator and art director, as a matter of fact.] “He died several years ago. But he gave me some advice before he left. He said, ‘I think you’re a strong painter, you could be a really great artist. But I don’t want you to go be an artist. I want you to get a job, pay your rent. If you have to get two jobs to pay your rent, do that. And I want you to do your art as a hobby.’

“He said, ‘I don’t mean like a hobby you do once a month or once a week. I want you to be like one of those crazy guys who build train sets in their garage night and day, or those guys that ride road bikes that get up at five in the morning to kill themselves riding 100 miles in those little outfits.’ He said, ‘Imagine if you put that kind of dedication and time into your art, really dive into it while you’re doing your other stuff that pays the bills. There might be a point along that way, people’ll start buying it. And if they do, then if it makes sense to leave your other job, then do it that way. That’s the plan.’ And I was like, let’s do it.”

Out on his own, Crawford did as Stermer suggested and took on two jobs, while treating art as a fanatical hobby. “I’d get up five in the morning, draw for an hour, go work eight hours as a printmaker. I’d come home, draw for an hour, then go wait tables for four hours. And I did that six days a week for the first year and a half after I graduated. No dating, nothing. All I wanted to do was build a life that I could be proud of,” Crawford says.

After a while, he started showing his work around Los Angeles. “I was getting my feelings hurt a lot by galleries. You know, who wants to give some 45-year-old ex-drug-addict a chance? ‘We don’t know who you are. You have no CV, no education. You can draw a little bit, so what? How do we build around that?’”

Gradually, though, things started picking up. “I got lucky,” Crawford says. “I started dating, fell in love with a great lady. Somebody offered me a little solo show. I quit waiting tables, because the art was starting to sell. Like, I’m not rich, but I’m making a living. And then my printmaking job went away, the owner sold the business. And I was left with the decision: go get another job, or become a full-time artist.”

Crawford went back to his alma mater and sought the advice of his mentor, Delancey Street’s founder and CEO Mimi Silbert. “I asked Mimi, ‘So what do you think?’ She said, ‘I think you should do it, it’s now or never. If you want to be an artist, be an artist. But this is gonna be hard. It’s gonna be really hard. And you have to promise one thing: when it gets hard, you won’t quit.’”

Mimi was right. It wasn’t easy. “It was terrible,” Crawford chuckles. “No, not terrible. I was doing what I loved. I was building up, but it was bit by bit. I had about $80,000 in credit card debt that was crippling and I couldn’t get out of it.” After he fell out with his gallery at the time, Crawford began using social media to sell his works directly to collectors. “I started doing print releases on my own, I started putting up my drawings on Instagram with one word that said ‘available’ and people started buying them. People would DM me and say, ‘I love this!’”

It was around this point that a new character began appearing in Crawford’s work. “I had this moment of clarity where I really fell in love with Pinocchio and his story,” he says. The puppet who wanted to be a real boy is gravely misunderstood and underestimated, Crawford reckons. “If you ask people who Pinocchio is, their first answer is a liar, he’s the little boy who told a lie and his nose grew. In fact, that’s five percent of the story.”

Crawford points out, “The other ninety-five percent of the story is, he’s brave, he’s courageous, he’s adventurous. He meets friends, some of the friends aren’t so great. He drinks, his friends who were drinking turn into jackasses. He gets swallowed by the whale, escapes. And he has all these life lessons along the way.” Clearly, a few echoes of the artist’s own tale there.

“I struggle with language,” Crawford says. “Art is my language. I try to tell stories through imagery, using my characters to tell my stories. It’s me manifesting my own thing.”

Indeed, the figures in Crawford’s paintings — anthropomorphic animals, characters from popular culture, and streetwear-clad children’s book escapees — seem to reflect Crawford’s default state of being: in a happy place, but in a mad rush to squeeze every drop out of the day.

“I work really hard — it sounds weird to say that, because everybody works really hard,” Crawford says. “My schedule is, I work in my studio, I’m there from ten AM to seven PM every day, I come home and there’s only a couple hours with my lady before she goes to sleep. Then I spend ten o’clock until one or two in the morning, working on my drawings at home. That is my schedule six days a week, all year long.”

Before he hits the studio, Crawford hits the gym. (The dude’s buff.) He’s vegan and obviously, post-Delancey Street, drug- and alcohol-free. “When you fix the person, then those things don’t even seem like something you wanna do,” he says. Besides which, it’s a myth that intoxication unlocks an artist’s creativity — in Crawford’s view, being constantly drunk or high can only hold you back.

“I have a dozen friends of mine that I think are more talented than me. But they can’t get out of their own way,” he says. “A stoner is going to be late and unreliable. A drunk is going to be late and unreliable. All the other drugs make you unreliable. If you’re going to make it as an artist, you can’t be unreliable.”

One can reliably say Crawford has made it. Our interview takes place during a pop-up exhibition of a dozen of his works, held at Singapore’s zhuzhy Mandala Club by leading auction house, Phillips. A couple of months after we speak, Phillips Hong Kong will auction one of Crawford’s paintings, H3RE HE COMES, for HK$2.1 million (more than a quarter-million US dollars).

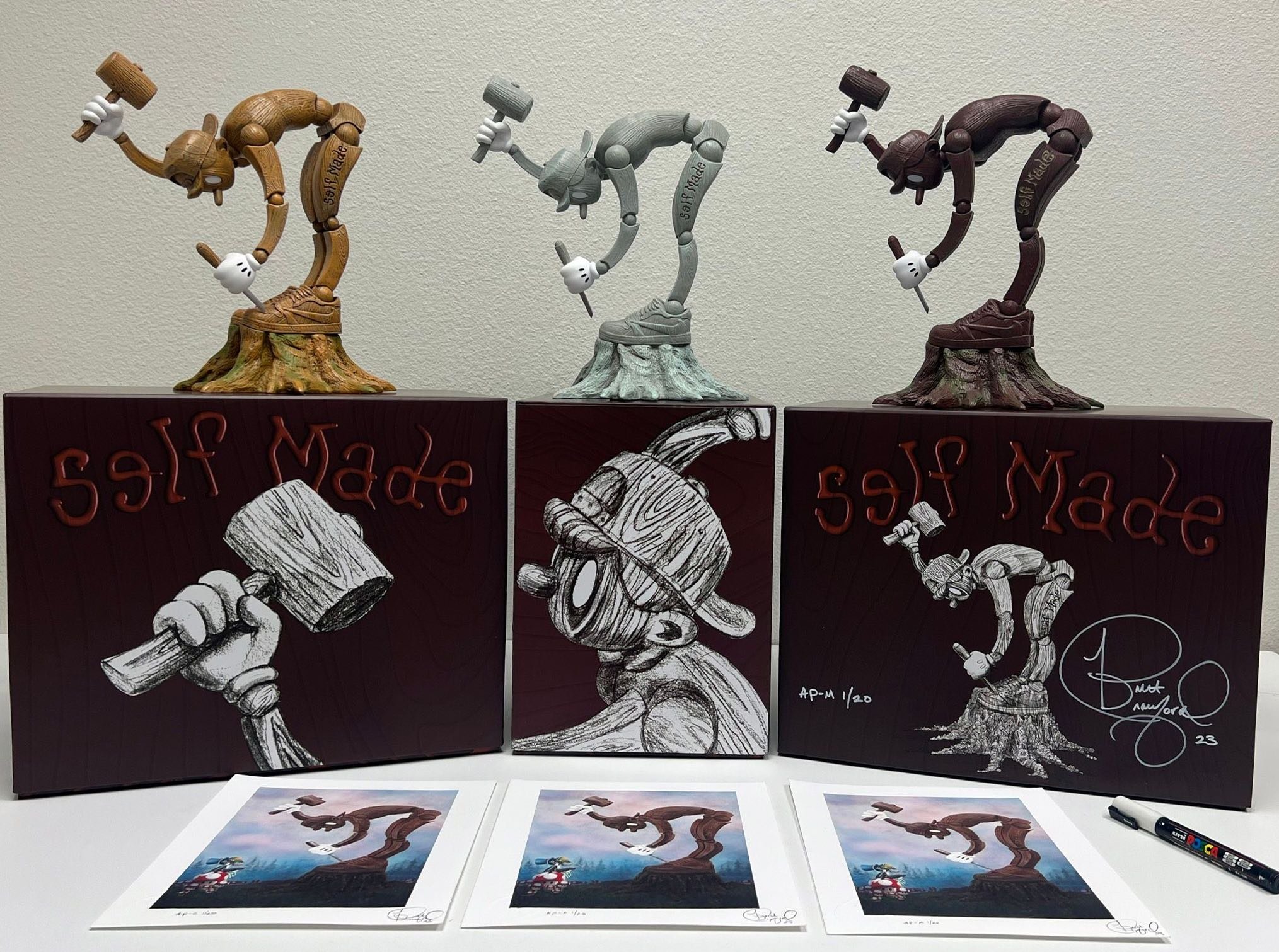

Continuing the clearly successful collaboration, Crawford’s first full-scale solo show in Asia will be held at Phillips’ new Hong Kong HQ from 9 to 22 June. WAST3D POT3NTIAL features not only sculptures and paintings, but more accessible collectibles such as limited-edition sneakers, art toys, screen prints and clothing.

“This is the best part of my life. Hands down,” Crawford says, his ‘can’t-believe-my-luck’ gratitude palpable. “I never thought that I could go from just being this kind of grimy lunatic, to having people like Phillips believe in me. It’s so rare to have people believing in you the way they do. I don’t take it for granted.”

Despite his talents, success and growing stature in the art world, Crawford is no Ozymandias. He recognises that real legacy isn’t manifested in statues. “I love making art,” he says, “but my hope is, when I’m gone, people will say that I was kind, that I was generous, and I was good with my community. That I helped other idiots like me fix their lives. I hope to be described as a good brother and a good father and a good son. And I hope they can say, he could also draw a little bit.”